Count Almásy, the protagonist of “The English Patient”, had been a real historical figure, I am delighted to discover on my first trip into the Western Desert. Lying west of the Nile, the Western Desert - the Egyptian Sahara - was explored and mapped in the earlier part of the twentieth century by Egyptian and European adventurers, like the Hungarian Lászlό Almásy

How easy it is to fall into the romanticism of that age, to search for the mythical oasis of Zerzura, the Lost Army of Cambysis. Our journey is certainly sparked by the quest for what those legendary adventurers left behind, even the rusted remains of the canned food they ate. We search, fruitlessly, for a little field in the dunes with no other features than its name, Regenfeld, bestowed by a German explorer to mark the extraordinary event that on the day he arrived there, it had rained.

No Bedouin or other nomads live in this wilderness that contains not a single source of water. With an average rainfall of only one millimeter a year, it is one of the driest places on earth. Camels cannot travel more than 300 kilometers without water and there are no springs or wells at the necessary intervals that would have allowed camel caravans to cross this desert. Once you leave the semi-circular road that connects the large oases of Bahariya, Farafra, Dakhla and Kharga, and go west, not a drop of water is to be found.

We venture into this wilderness in four-wheel-drive vehicles – the modern day ships of the desert – and that too is a complicated logistics operation, as the jeeps have to carry their own supplies of water and fuel in addition to food and equipment for the entire duration of the trip. The drive through the high dunes of the Great Sand Sea is carefully saved for the final part of the trip, when the jeeps are considerably lighter and less likely to sink into the sand.

I am a hiker at heart and hesitated to join a trip based so completely on traveling in jeeps. I had always believed that riding in motorized vehicles would break up the gradual unfolding of time which to me is the essence of a trek, that it would turn natural phenomena into ‘sights’, isolating them from their natural context, losing what is unmediated, raw and unique. But I am a lover of deserts, and I knew that the only way I could get deep into the vast Egyptian Sahara, was by jeep.

After a stay in the oases of Farafra and Dakhla, with their ancient mud-brick buildings and jungles of date trees stretching for kilometers on end, our group finally leaves the road, and all signs of life, on a six-day journey into the Western Desert. We are twenty foreign travelers – mostly Israeli geologists, myself and three other women friends from Jerusalem, two Mexican brothers, in addition to an Egyptian staff of eight. One of the geologists remarks, this is a desert entirely formed by wind and sand, so unlike the rocky deserts we know in Israel and the southern Sinai, with their deep canyons and rugged mountainsides resulting from the flow of water or tectonic upheavals. Even the flat, limestone plateau of the E-Tih desert in the northern Sinai is carved by canyons.

Hikes in those deserts, are, in a sense, “water hikes” in canyons hollowed by water that is no longer there. On my hikes in Israel’s deserts, I often envision that I, the hiker, am the water, flowing through the narrow gorges, going down the falls, cascading over the boulders in the streambed. Here, in the Western Desert, the flat, sand covered distances are enormous, interrupted only by isolated outcrops of rock that look like islands in a tranquil sea. If we are to hike, we will have to walk for days without “getting anywhere”.

It is the infinite expanses of this desert, the horizons you can never reach, that conjure up the image of an ocean. Add to this the undefined spaces, the scarcity of landmarks that would ease orientation and save you from drowning in the sands, while the fata morganas shimmering in the sun intensifies the illusion of distant bodies of water.

The sea in this desert is not only an image or a sensation - there are testimonies of primordial lakes and seas everywhere in this landscape that is so thoroughly devoid of water. Entire skeletons of Eocene whales, some, with vestiges of feet and toes, lie spread out in the sands in Wadi Hitan, the Valley of the Whales, where we camp on our very first night after leaving Cairo. There are tens of fossils of other large aquatic animals strewn all through the valley, and mangrove forests that had turned into intricately sculpted rocks are still standing upright on the bottom of the vanished sea.

Deeper into the Western Desert, we spend one night in a large, shallow depression with its rust colored bottom looking like cracked and hardened mud - the remains of an ancient lake. We see grinding stones that were found here together with other stone-age tools and artifacts, attesting to past human settlement along its shores. Walking at sunset with the long shadows cast by the burnt red mud sculptures scattered in this plain, they seem like shark fins cruising above the surface, or bodies of whales breaching the sandy surface. A large rounded rock looks like a portly walrus.

Little by little I begin to suspend my aversion to jeeps, realizing that they enable us to sail deeper and deeper into the desert sea. I recognize that the frequent rest stops, or the long breaks for lunch, elaborately prepared by our gourmet chef, give me the opportunity to gather myself together, to regain my strength, to be centered again. I am able to take long walks at sunset while camp is being set up, and wake before dawn to watch the sunrise. I walk after breakfast, as the jeeps are being loaded, which can take over an hour. And so I let myself go, feeling the uninterrupted thread of the journey, despite the travel in jeeps, as I fall into step with the rhythms of the sun, the moon and the distances.

Earlier, along the way, we saw large trunks of petrified trees lying in the sands, while on some of the rocky outcrops there are drawings of giraffes and other savanna animals incised into the soft sandstone, testifying to past vegetation. There were a few tracks of foxes, perhaps of a lizard or two and the skeleton of a small snake and of some birds. Now there is not even a fly. On one of my walks, while looking for unusual stones, I come across a large, lone insect. I mark a circle around it in the sand, drawing a line with my shoes as I walk towards the ecologist in our group, who identifies my find as a praying mantis, not able to hide his excitement about finally seeing a living creature in this arid wasteland.

Instinctively, I begin to collect stones, something I have never done before. Little stones, stones that I can keep in my pockets, hold in my hands and caress. It begins while we are still staying near the oasis town of Farafra, and explore the White Desert, with its milky mushroom formations and cream-colored sands that seem to be covered by a blanket of white snow. I am struck by the small, irregular pieces of black, ironized stone that I think, at first, are animal droppings on the desert floor, revealing hints of life. After that, I become more and more entranced by the forms, colors and textures of the desert stones, and cannot keep my eyes off the ground on my walks.

Perhaps keeping my eyes on the ground and searching for stones is my way of connecting to the vastness of this desert, where there is no middle ground - only endless vistas or very near close-ups. It is like the taking of photographs, which, beyond the desire to bring back mementos, is, for me, an act of focusing on something tangible, coming close and touching it, since it is impossible to capture the desert’s immensity.

The stones in this desert come in concentrations of the same kinds and shapes. In one place, there are scores of tiny iron balls, the size of marbles; at another, we see thin, elongated fingers with intricate designs engraved on their surfaces that turn out to be petrified remains of squid-like marine animals. There are sites with larger crooked forms, also ironized, with bulbous extensions, perhaps fossilized roots, or sites with glistening black pyrite sheaths, over a lighter brown inner core. There are collections of perfect spheres, the size and color of boiled egg yolks, and ochre clumps with minuscule cubic patterns and craggy hollows, like skulls or brains of small animals. The most evocative are the mounds of brown, smooth forms, with thin, curving labia.

One day, while searching for my little rocks in the sands at one of our lengthy lunch stops, I come across a number of shark teeth that are at least 40 million years old. They are just lying there, on the desert floor, all in one place, and I happen to come across this treasure trove. An ancient sea had dried up, the sharks had perished, and their teeth, hard as stone, remained here, for me to find. Yes, this is another confirmation that those infinite surfaces of sands do not just look like an ocean.

The next day I make a new, even more thrilling discovery. On my early morning walk, near the place where we camped that night, I notice a few small circles in the sand, about fifteen centimeters in diameter, lying at the base of some small rocks. I start to dig around them and six or seven very unusual earthenware pots start to emerge, standing upright next to each other. There are also flat, round pieces with a hole in the middle that fit as covers, while the strange, roughly-made pots have no bottom at all. Could they have been vessels for burning incense, as someone offered, and this had been a site of ritual worship? I take their photo and cover them up with sand again, for someone else to find. On my return home, further research identifies these pots as “Clayton Rings” first found by Patrick Clayton in 1931 – yet the mystery of their function remains to be solved.

I am exhilarated that I was able to find something so significant and rare in the heart of this complete nothingness. Something I was not even looking for. I would not have the presumption to search for the Lost Army of the Persian general Cambyses that disappeared to the last soul in the Great Sand Sea, as recounted by Herodotus, nor the legendary Lost Oasis of Zarzura – why should I, of all people, be able to find such elusive treasures that others spent years searching for? I was only looking for my humble stones, even though my imagination had been spurred by these myths of the early explorers. My ability to find a definite place in the seemingly undefined and endless spaces of the desert, gave me a new sense that I had not known before, anchoring my personal being to the immensity of this desert, indeed, of the universe.

I secretly hope we will get to Gilf Kebir - called The Great Wall because of the high cliff that surrounds this raised plateau – even though I know it is not a part of our planned trip. I dream of reaching Wadi Sura, a gorge on the western side of this plateau, with the rock drawings in the legendary Cave of the Swimmers, who once swam playfully in what is now a barren wasteland. We can vaguely distinguish the Great Wall in the far distance, stirring my hopes, but it is too far for this trip, says our expedition leader. I promise myself that I will return on a longer journey that goes up those cliffs, to hike through their canyons and to continue to Gebel Uweinat, Egypt’s highest mountain, at the very point where Libya, Egypt and the Sudan meet. Two years later, I am able to do this – but that is another story.

The furthest south we get on this trip is a huge field of meteorite craters, the largest concentration of meteorites on earth, which is a delight for the geologists in our group. Then we turn north, heading towards Abu Balas, ‘Father of the Pots’ - a sandstone hill in middle of the flat sands, known for a collection of some 400 huge earthenware jars that had been found there. Some fragments of these jars - made on potters’ wheels - are still scattered at the foot of the hill, others are in museums or were simply stolen. Archeologists dated these pots to the time of the Pharaohs and speculate that this was a place where water was stored for ancient caravans, half way between Dakhla - 240km away - and the springs in the wadis of Gilf Kebir (the lost Zarzura?), on their way to the Kufra Oasis in Libya.

Abu Balas is a prominent landmark in this desert, but I am glad that we continue past it that evening to look for another campground. We find a sheltered bay, surrounded by sandy slopes with a scattering of black rocks, much like the meteorite craters, but more elongated and open at one side. We camp at the foot of an island-hill in the safety of this sandy harbor. That night, by the faint light of the moon, I go on a long walk with my three friends from Jerusalem, all avid hikers like myself. We walk towards the entrance of this bay, trying to distinguish the shadows of islands out in the open seas.

I love to walk in the dark, without a flashlight, relying on my night-vision, which I believe has more to do with trusting all my other senses than with my eyes. Once, when I had gone out alone in the middle of the night, as I did often, the camp was suddenly no longer visible. I was never afraid I would not find my way back, as there were silhouettes of rocky hills that I had taken note of, and through which I could orient myself in the dark. It was just an incredible feeling to be out alone in the wilderness, without having to fear human or animal predators, because I knew none could possibly live in this desert. Perhaps I was playing with the sensation of getting lost - walking the thin line of tempting fate, feeling the secret pleasure of letting go, like when you fall asleep, which is perhaps, a ‘little death’ – yet safely knowing it is not for real.

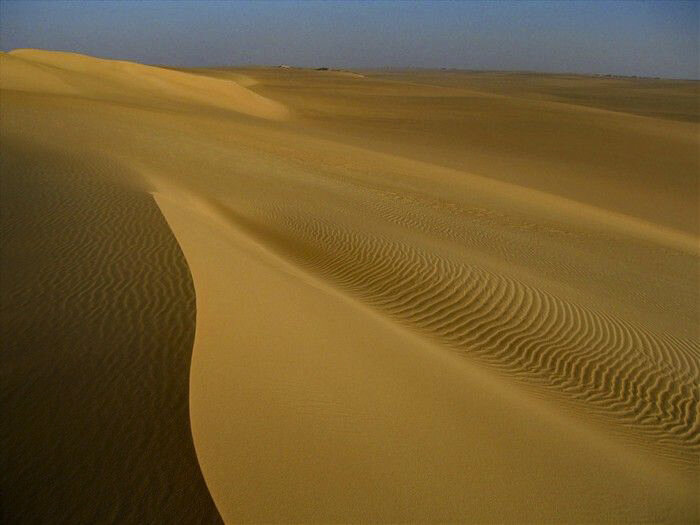

On the day before last, we enter The Great Sand Sea, navigating through its giant surges of sand. We have already encountered sand dunes before, forming the rims of the meteorite craters and in our sheltered harbor camp, but here is a world made up solely of sand. This is where you get lost, where even the few rocky landmarks, like islands in the sandy plains, are absent, and everything around us is sand, unadulterated sand.

The Great Sand Sea is the legendary desert associated with the ‘real’ Sahara – even though only an insignificant percentage of the Sahara is covered with dunes. It was here that the army of the Persian general Cambyses vanished without a trace. And possibly where Antoine de St. Exupéry and his co-pilot crashed their plane on a flight from Paris to Saigon. That was in the nineteen thirties, when instruments to measure one’s bearings were still rudimentary, and on a dark, stormy night, without visibility, the aviators did not even know whether they had crossed the Nile or not. The two men walked for days with only half a liter of water to share, ultimately living to tell - of delusions and coming near death. Evidently, it is this experience of being totally lost in the desert that later inspired St. Exupéry to write The Little Prince.

I am not sure I would have persevered if I had been wrecked in that sea of nothingness, where there is no way of knowing if you are only one day or weeks away from human habitation, and in which, of all possible directions, you should choose to walk. The temptation to give up and fall into eternal sleep, lured by the serpent of the Little Prince, would be too great. And then I remember my discoveries in the middle of this desert - finding something against all odds in the middle of nothing – which enables me to see that the search in a seeming void need not be futile. Yes, now I am beginning to understand what gave those men the faith to persist.

On the eastern shores of the Great Sand Sea, the dunes are linearly aligned in long north-to-south ridges, like huge tsunami walls of water, one following the other. In principle, you might be able to orient yourself, if you know how many dune-waves you have crossed – but deeper into the Sand Sea the valleys between the crests become narrower and narrower and you are certain to lose count of how far into the dunes you have ventured.

It proves to be quite an act to cross the high ridges, and the jeeps get stuck several times in the sands right at the peak of the dune and have to back up all the way down to regain momentum for another try. I love it when the jeeps get stuck, as that gives me time to get out and walk around, looking at the sands untouched by human feet, marveling at the ripples on the dune-bodies that begin to take on human forms, especially in the long shadows of the late afternoon. I delight in running down the dunes and watch the sands slowly spill down the steep slopes behind me, like little waterfalls, continuing long after I have disturbed their immaculate stillness.

This is a world of total immersion in sand, with nothing else in view but the dome of the sky with the sun and the clouds, the moon and the stars. A traveling companion had noticed earlier how close the sky seems to be in this desert – she had not seen the movie “The Sheltering Sky”, set in the Algerian Sahara, where that same remark is made. At first I thought it was because of the horizons that are always visible in the flat sandy plains, sometimes in all directions – but it has perhaps more to do with the clouds that you can almost touch – as even in the midst of the dunes, where you cannot see the horizon, the skies are near.

It is here that you are called upon to surrender to the sands – there is no other choice in this all-encompassing ocean. You have to dive in and swim, let go of everything else you left behind on the shores, just be here amid the rising and falling waves. Swimming is a rhythmic act of going under, and coming up again for air. You have to surrender to the water when you go down, trusting you will surface again. That too is a little death. Just as you need to go up, for air, for life, you also need to go down - for images from the unconscious, for memory, for fantasy. To face the deep, and come back fuller, richer.

Only a few years before this journey into the Western Desert, did I become a swimmer. I used to fear putting my head in the water while doing the breaststroke, a fear that stayed with me from early childhood until I finally learned to let go, which is an act of maturation. Now I can do the crawl for two to three kilometers, going up to breathe like a dolphin, and plunging back into the water, as the sound of the plunge and the noises above water are damped, again and again. No thoughts - they are washed away, there is just me and the water, my body suspended in liquid space, my skin brushing against the water’s resistance, not taking it for granted, the way we often take for granted our movement in air.

The longer I am in the desert, the more I feel connected - to the dunes, to the tenderly embracing skies. After six days, I am becoming merged with the surrounding sea of sand - I have become a part of it, which is what happens to me when I swim. Like a fetus in the waters of its mother’s womb, I am being nourished, readying my body and spirit for the inevitable return to ordinary life.

Before and after our journey into in the deep desert, we stay in a small, cozy hotel, at the rural outskirts of the desert oasis of Farafra, 550 km southwest of Cairo. In the cultivated fields behind the hotel, there is a hot spring with an irrigation pool, which we discover on an early morning walk on the day before we leave for the deep desert. The first thing I do when we return from our journey is to jump into the hot waters of that pool, straight from the jeep. All the dust and sweat I have accumulated in the waterless past six days, is washed away instantly, mixing with the ferrous oxide that colors the pool’s concrete walls red. In this steaming irrigation pool at the desert oasis, I am swimming in the desert – literally.

*********